One of the most popular American movies of the 2000s is The Devil Wears Prada, a comedy set within the cut-throat world of fashion at the fictional magazine Runway. Meryl Streep’s iconic character Miranda Priestly pays homage to Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour, as she plays the villain to Anne Hathaway’s fish-out-of-water Andrea Sachs.

Andrea is a true fashion novice who accepts the role of Priestly’s assistant with reluctance and desperation. She spends the first part of the film openly criticizing the fashion industry. That is, until Stanley Tucci’s character Nigel, a Runway editor, delivers an eye-opening lesson on what makes fashion so culturally significant.

In the clip below, we see Andrea seeking a bit of empathy and guidance from Nigel after she’s failed, again, to live up to Priestly’s incredible expectations. Much to Andrea’s chagrin, Nigel explains why it’s not her ineptitude that’s worsening her professional relationship with Priestly but her blase attitude towards the industry itself.

“Don’t you know that you are working at the place that published some of the greatest artists of the century? Halston, Lagerfeld, de la Renta. What they did, what they created, was greater than art — because you live your life in it,”

Nigel tells Andrea.

The scene is pivotal because it marks a change in Andrea’s perspective as she learns to adopt appreciation for the artistry of fashion and the significance of the fashion magazine as a cultural touchstone. Nigel emphasizes his point by stating,

“You have no idea how many legends have walked these halls. And what’s worse, you don’t care.”

One of those legends includes French fashion photographer Patrick Demarchelier, whose name comes into play regularly throughout the film. In this way, the film reflects the symbiotic relationship between fashion design, photography and publication. All three play a crucial role in making fashion greater than art.

See how Demarchelier and the groundbreaking photographers below have helped define the world of fashion, documenting the work of legends who walk the halls of fashion magazines.

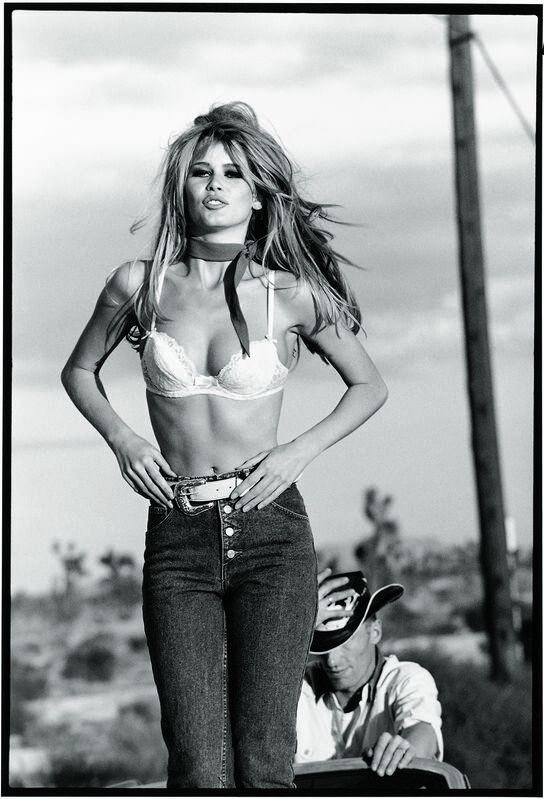

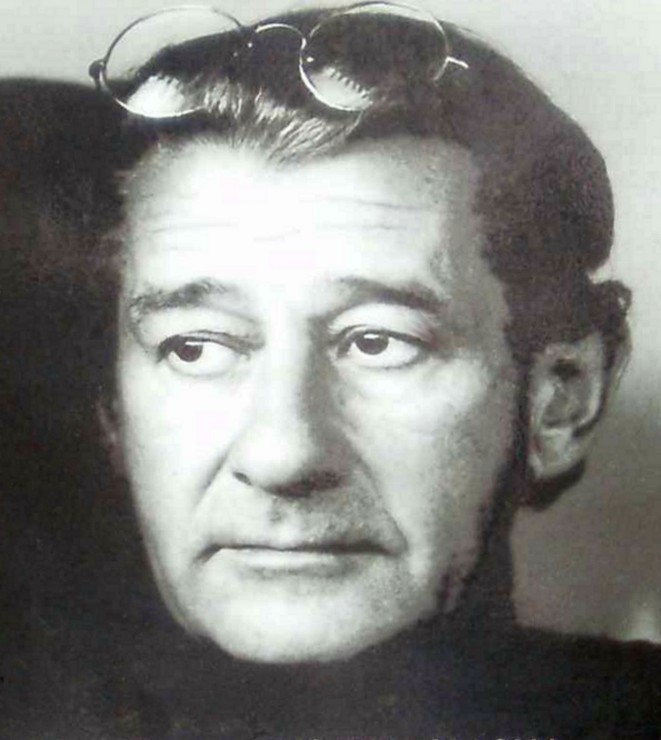

Patrick Demarchelier (b. 1943)

“The idea is always the same: Let people be themselves. You don’t want them to pose, or be self-conscious. The accident is the best picture — the one you’re not expecting.”

Demarchelier first picked up a camera when he was 17 years old, having received a Kodak Eastman for his birthday. He documented intimate moments of his life with family and friends before moving to Paris at age 20 and working at a photo lab and printing newspaper photographs. He soon became an assistant to Hans Feurer, a Swiss fashion photographer who worked for Vogue. It marked Demarchelier’s entry to the world of fashion where he would later become an iconic documentarian.

Demarachelier has moved consistently between photographing advertising campaigns for brands like Dior, Revlon, GAP, Chanel, Calvin Klein and Louis Vuitton, and publishing photos for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, Newsweek and Rolling Stone. Unlike many of his contemporaries, and even other groundbreaking fashion photographers, Demarchelier’s aesthetic is not defined by a signature style or recognizable look. That’s because he focuses on capturing his subjects just as they are, however they appear, in whatever setting they are. He doesn’t limit his photography to preferences of environment, themes, moods or technical approach.

One of the most noteworthy chapters of Demarchelier’s artistic career is the time he spent as Princess of Wales Diana’s personal photographer. She’d been intrigued by his ability to document visual narratives, and he had always admired the way she smiled most genuinely when captured by paparazzi photographers. Demarchelier is responsible for capturing images of Diana that warmed the hearts of viewers around the world, in a small way helping her become “the people’s princess.”

Demarchelier is considered one of the most important photographers that Wintour looks to for Vogue (hence his name’s constant references in The Devil Wears Prada). She has said of him,

“Patrick takes simple photographs perfectly, which is of course immensely difficult. Working without ornate settings, often in black and white, he makes attractive women look beautiful and beautiful women seem real.”

Annie Leibovitz (b. 1949)

“Everyone has a point of view. Some people call it style, but what we’re really talking about is the guts of a photograph. When you trust your point of view, that’s when you start taking pictures.”

Even though she’s considered one of the most celebrated photographers of our time, American photographer Leibotivitz didn’t intend to become one at all. She was raised in Connecticut, studied painting at the San Francisco Art Institution and planned to become an art teacher. She took photography classes at night. But when she began working at Rolling Stone, she perfected her craft and established her niche.

She is best known now for capturing dramatic and stylized portraits of celebrities, aiming to create visual narratives that reflect her subject’s depth of personality.

Leibovitz has contributed lasting images that stir conversations around celebrity and pop culture. Her portraits have covered Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair and Vogue numerous times. Among her most iconic portraits include a pregnant and nude Demi Moore, Whoopi Goldberg in a bathtub full of milk, RuPaul Charles in a crystal-beaded leotard, Meryl Streep wearing a cosmetic facial mask and Caitlyn Jenner seated on a stool and wearing a corset. Other celebrities that have sat for her include Adele, Woody Allen, David Beckham, Hillary Clinton, George Clooney, Miley Cyrus, Johnny Depp, Queen Elizabeth II, Rihanna, Oprah Winfrey and Anna Wintour, among many others.

It’s fair to say that Leibovitz is a household name, state-side. Her images both typify and influence the people at the front of the pop culture zeitgeist. She’s published numerous photo books, including Women, American Music, Annie Leibovitz at Work, Shooting Stars: The Rolling Stone Book of Portraits and several collections of portraits.

Corinne Day (1962-2010)

“What I found interesting was to capture people’s most intimate moments. And sometimes intimacy is sad.”

Day entered the fashion industry with a remarkably original backstory. The British photographer was raised in London by her grandmother, and her mother had owned a brothel. She wrote in an autobiography,

“I left school at 16 with barely any education. All I wanted to do was travel but I had no money. I got a trainee job at a bank which made me laugh because my dad was a professional bank robber.”

She began dating a man when she was 18 who traveled internationally as a courier and loved photography. She secured a job as a courier alongside him, worked as a fashion model, and eventually learned how to use the camera herself.

In 1989, Day returned to London and began photographic work with The Face magazine. Her aesthetic was radical by the fashion industry’s standards — she photographed everyday London youth, untouched and unstyled, who were deeply embedded in the grunge scene. When she was introduced to 15-year-old Kate Moss, an undiscovered model who seemed an unlikely fit in the fashion industry, she instantly felt connected to her. In July 1990, her photo of Moss on the cover of The Face catapulted both women to notoriety.

The mid-90s marked a turning point in Day’s personal and professional life. After suffering a collapse, she was diagnosed with a brain tumor and had to seek treatment. For the sake of financial support, she delivered fashion photos that were less gritty and more glossy. She shot for Vogue, Telegraph Magazine, i-D, Nova, Mixte, Rolling Stone and Elle. She still retained echoes of her original aesthetic, though, and didn’t completely lose sight of her roots. She photographed celebrities like Moby, Beck, Helen Mirren, Sofia Coppola and Tilda Swinton. In 2010, she passed away from cancer.

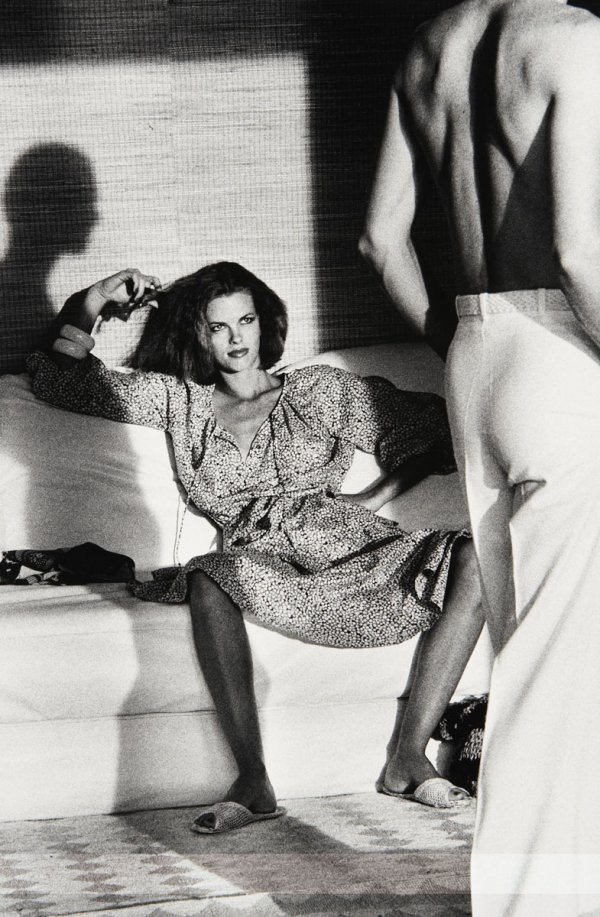

Paolo Roversi (b. 1947)

“Photography goes beyond the limits of reality and illusion. It brushes up against another life, another dimension, revealing not only what is there but what is not there.”

Born in Ravenna, Italy, Roversi discovered his passion for photography as a teenager. He set up his own darkroom at home and dedicated himself to apprenticing a local professional to understand the craft. Just 10 years after being bitten by the shutterbug, he began working as an assistant to British photographer Lawrence Sackmann. Shortly after, he began working in photojournalism and providing work for the Associated Press. His first assignment was to cover Ezra Pound’s funeral in Venice.

Roversi opened a portrait studio in his home town in 1970. By chance, he met Peter Knapp, Elle magazine art director, at this time period. When Knapp invited him to Paris in 1973, Roversi accepted and soon called the city home.

He began forging his career in fashion photography, establishing his signature style with classic portraiture that was made dreamy by creative lighting techniques and manipulation. His work is simultaneously elegant and dark, and ethereal and raw.

“The presence is much stronger, much deeper — in the aura, in the eyes, there is something. Maybe the soul is coming into the eyes.”

Between advertising and fashion editorials, Roversi has become a prominent name in the fashion world. His commercial work includes such clientele as Dior, Valentino, Yves Saint Laurent and Alberta Ferretti. He’s produced work for Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, i-D, Interview, Marie Claire, Vogue and W., among others. He continues to work and live in Paris.

Fashion photography is far more than a simple snapshot of garments. As Nigel describes in The Devil Wears Prada, fashion itself is “greater than art because you live your life in it.” And the artists behind the lens contribute just as significant a point of view as those who craft the clothing. These photographers above are each known for their own take on documenting this incredibly rich field of design and artistry, punctuating the significance of a sartorial narrative through their innovative modes of visual documentation. Want to read about more of them? Check out parts one and two!