France is often described as the standard-bearer of the world for high-end culture and fashion, representing the ultimate in effortless sophistication. Iconic designers present the very latest of designs twice a year, ushering in the next chapter of sartorial ideals that spark the musings of designers everywhere. What coincides neatly with this is the image of the chic Parisian woman who translates these visions into everyday class and style. Countless blogs, videos, and tutorials exist to teach audiences how to mimic her essence. She’s the epitome of the fashionable feminine with a tall, slim silhouette and prominent bone structure.

Yet behind this iconic imagery — of the photographed model who embodies the fashion world, and the everyday French woman who’s watched with envy from afar — is a challenging reality of visual media representation that’s in the throes of change.

French new legislation

In 2015, the French government passed a law stating that in order to walk the runway, models needed to provide a doctor’s note showing proof that they had a body mass index of at least 18. Failure to comply can result in a fine. The goal is to scale back the influence of images of extremely thin models. It’s been part of the country’s effort to rein in the prevalence of eating disorders and more responsibly manage unrealistic and unhealthy beauty standards. The image of the Parisian woman, it seems, has gone too far with her slimness. Italy, Spain and Israel followed suit with the same runway model bans.

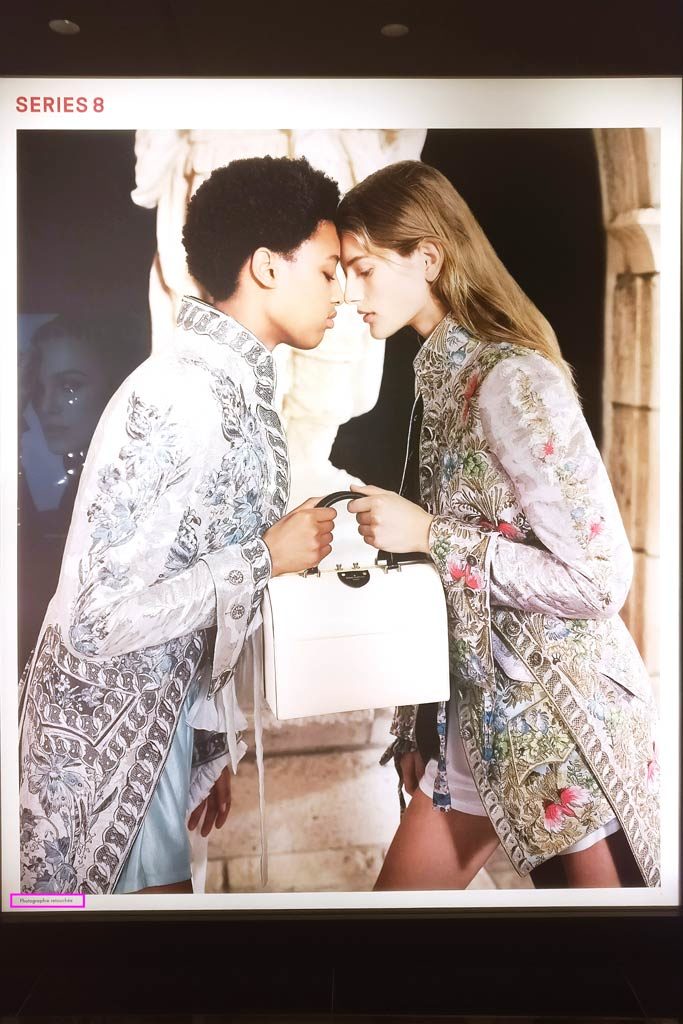

Two years later, the French government passed another law with a similar goal: any commercial photograph showing bodies that have been digitally altered to appear thinner or thicker must also have a notice of “photographie retouchée,” meaning, “retouched photograph.” Failure to comply could result in a fine of 75,000 euros, or up to 30 percent of advertisement funds.

The legislation has been championed by French politicians, including former health minister Marisol Touraine. Touraine expressed, “It is necessary to act on body image in society to avoid the promotion of inaccessible beauty ideals and prevent anorexia among young people.” Numerous articles at the time cited alarming statistics about the epidemic of eating disorders that uniquely affects France:

- About 600,000 young people are believed to suffer from eating disorders in France [as of 2017]

- Eating disorders are reportedly the top cause of death among 15- to 24-year-olds in France, making it the second leading cause of death in that age group [as of 2017]

- Anorexia affects between 30,000 to 40,000 people in France, 90% of whom are women [as of 2017]

- Seventy percent of girls ages 10 to 18 report that they define perfect body image based on what they see in magazines [as of 2015]

- Out of all Western Europeans, French women have the lowest BMI, at 23.2 [as of 2009]

- 11 percent of French women are considered “extremely thin” [as of 2009]

Altogether, the content paints a portrait of French beauty ideals that are more damaging than desirable.

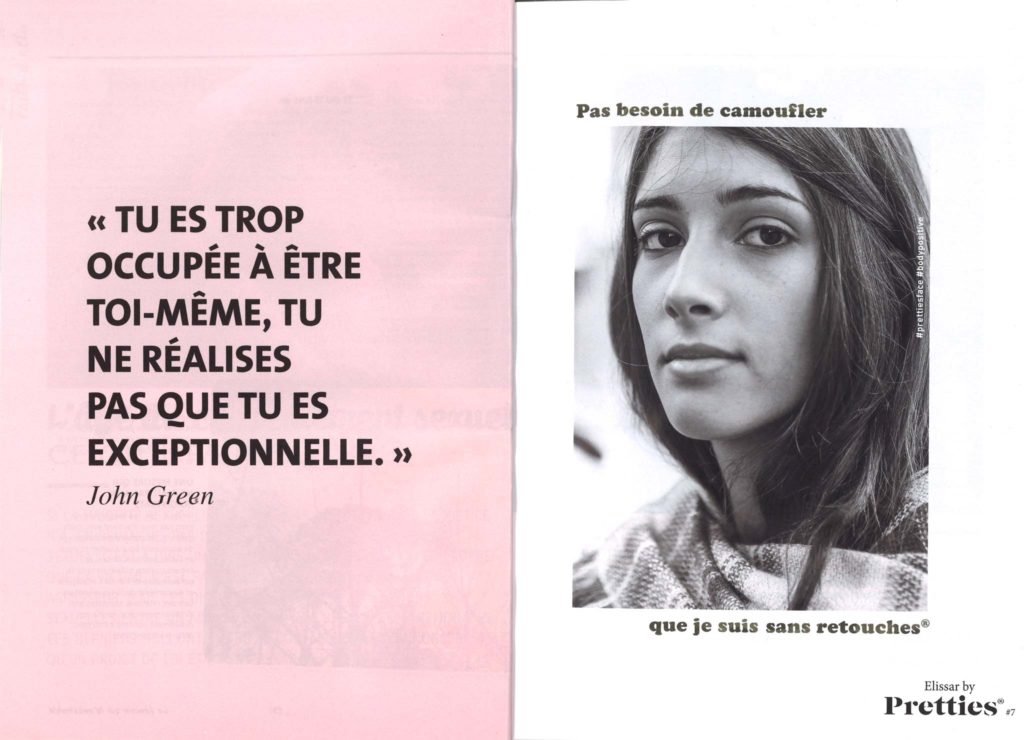

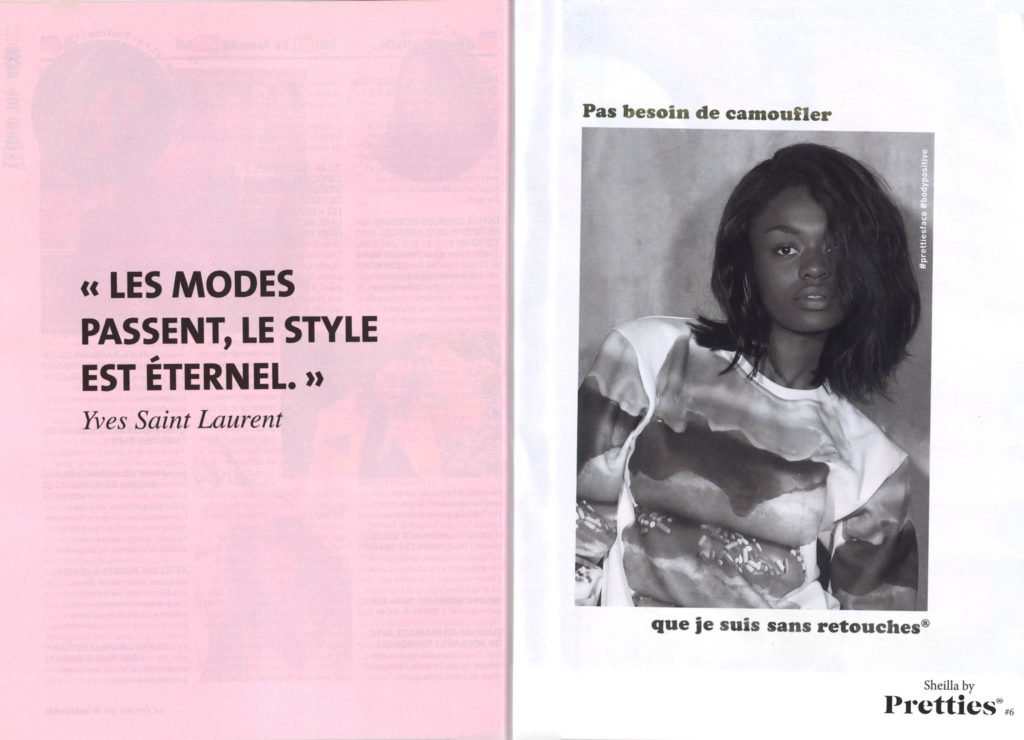

Developments towards body authenticity

Across the Atlantic, American brands made strides in the spirit of body positivity and authenticity as well. Getty Images announced that year that they would no longer accept creative visuals and stock photography that featured altered body shapes (despite acknowledging that retouched photos are rare in stock photography). Getty spokeswoman Anne Flanagan remarked, “Our perceptions of what is possible are often shaped by what we see… Positive imagery can have direct impact on fighting stereotypes, creating tolerance, and empowering communities to feel represented in society.”

The push for body authenticity and accurate representation often draws praise from those within the body positivity movement who are pleased to see “regular women.” At long last, real women can see themselves represented in fashion via magazines, social media, commercials and print advertising. And if they don’t see themselves because the image has been retouched, they can rest assured knowing that the image they’re seeing isn’t even accurate.

But questions remain, rather quietly in the background of the fashion and beauty industries: Is labeling a photo as retouched an effective means of preventing eating disorders? Have eating disorders slowed or even fostered the sort of body positivity that proponents work towards? Do people feel better about themselves when they see that an image has been altered?

The background of eating disorders

Answers to these questions run the gamut. Eating disorders are complex psychological conditions that can arise for a number of reasons. Traumatic experiences, genetic links, sports performance requirements, and family dynamics can all be precipitating factors, according to the Eating Recovery Center. The center recognizes that culture plays a role in causing eating disorders, too: “Every day, we are besieged with messages about beauty, unrealistic body images and fad diets.”

That the overwhelming pressure to be thin can trigger body dissatisfaction and disordered eating habits isn’t news. But it just so happens to be what proponents consistently use as their main argument for skinny-model bans and retouch labels. Findings from clinical research tell a slightly different story.

Studies & discussions about the retouching label

In a study conducted by Elisa S. Danthinne and Rachel F. Rodgers, they found no empirical evidence that supports the usefulness of retouch labels in slowing body dissatisfaction and eating disorders. In fact, they have the opposite effect. They write:

“A majority of research evidence indicates that single exposure to the presence of a label alone is not effective in improving body image, and can in fact be harmful by increasing comparison tendencies. This finding does not seem to have reached many policy makers and players in industry, who have continued to favor labeling practices.”

Another study, conducted in 2015 before the bill became law, arrived at similar conclusions. Belinda Bury of Flinders University conducted four experiments about the effect of retouch labels, one of which included giving subjects an informational message that preceded advertisements. She concluded:

“The thesis found no overall benefit from the use of either generic or specific disclaimer labels appended to thin ideal fashion magazine advertisements. Rather, specifically worded disclaimer labels actually directed visual attention toward body areas specified as altered, with this increased visual attention itself resulting in increased body dissatisfaction and being worse for women high on trait appearance comparison. The presentation of digital alteration information before exposure to advertisements with disclaimer labels did nothing to enhance the effectiveness of the labels, nor did instructional set.”

Interestingly, a number of proponents of skinny-model bans and retouch label legislation who work in the field of eating disorders recognize the lack of effect. Tom Quinn of Beat — a charity geared towards eating disorders — told the BBC, “It’s simplistic to suggest that looking at Photoshopped images will cause eating disorders. But many people who look at altered images have low self-esteem.” He added, “We support any measures that contribute to a society having a healthier view of body types and everyone being more aware of which pictures have been touched up.”

Last year, Dr. Luke Evans MP, of England, proposed the Digitally Altered Body Images Bill, which would require a logo to indicate a person’s face or body has been digitally altered. He wrote, “Knowledge of when an image has been digitally manipulated will have positive mental health benefits for a wide cross section of our society affected by body image.” In support of the bill, the UK’s Mental Health Foundation responded:

“Labelling edited images is just one approach and unfortunately there is a scarcity of research to show it will solve the overall problem. For labelling (or any other industry change) to work, it will need to be co-produced with experts by experience and its implementation needs to be carefully evaluated.”

The timing of Dr. Evans MP’s bill is notable. He introduced it in September, five years after the passage of France’s skinny-model ban and three years after the passage of its retouch label law. Just one month prior, in France, researchers conducted an online cross-sectional study of college students at the University of Rouen-Normandy. The aim was to identify the characteristics of eating disorder categories and help- and care-seeking among college students. They surveyed nearly 1,500 students. They concluded:

- The prevalence of likely cases of eating disorders was 24.8 percent, with a higher prevalence in female students (31.6 percent) than male students (17 percent).

- Of that 24.8 percent, 13.3 percent were considered to have a bulimic eating disorder, 8.6 percent hyperphagic eating disorder, and 2.9 percent restrictive eating disorder.

- The pressures of academic performance caused significant stress, which causes “a change in the habits of young people related to their practice of physical activity and food.”

It bears repeating what is widely known about eating disorders: They’re incredibly complex and can have several precipitating factors, not just visual media. How much can we reasonably expect a retouch notification to achieve — especially if studies show that it has the opposite effect? And why do politicians keep introducing these bills if they don’t accurately address eating disorder prevention and awareness?

Back in 2009, Valérie Boyer, then a member of the French parliament who also has a background in health administration, drafted a bill to address digital retouching that would require all advertising images to carry a retouch label. She said she was inspired by watching her teenage daughters manage the pressures of having a thin body and perfect skin. In a New York Times article, she remarked, “If someone wants to make life a success, wants to feel good in their skin, wants to be part of society, one has to be thin or skinny, and then it’s not enough… one will have his body transformed with software that alters the image, so we enter a standardized and brainwashed world, and those who aren’t part of it are excluded from society.”

In that same article, Anne-Florence Schmitt, editor of Madame Figaro magazine, called it a “fake debate.” Former model and clothes designer Inès de La Fressange said it was “demagogic and stupid” because the causes of anorexia are complex. And French fashion photographer Dominique Issermann said that Boyer has not only “misunderstood the problem” but the nature of photography altogether. “There is this illusion that photography is ‘true’ … As soon as you frame something, you exclude something else,” Issermann said.

She then added a poignant detail about the inherent limitations of a single snapshot, seeming to gesture to the notion that whatever is in the frame doesn’t tell a complete story: a photograph is “a piece of reality, but the reality of the world is different.”

Current developments during Covid-19

As you can see in the video above, eating disorders have resurged and become even worse as a result of the pandemic. Comparisons of the numbers of the recent years cannot give any neutral information about the effectiveness of the retouching label. But coupled with the studies above, reality seems to favor the underlying psychology that precipitates eating disorders, as opposed to visual media being the main culprit. If stressful, overwhelming and traumatic situations can trigger setbacks and prompt new body dissatisfaction or disordered eating habits, how much can we expect a retouch notification to accomplish?

Do you have any suggestions, additions, is this post out of date, or have you found any mistakes? Then we look forward to reading your comments. You are welcome to share this post. We are very grateful for every recommendation.

Do you want to read more about the execution of the french law? Find out more in our previous articles Presence analysis of the retouching label “Photographie retouchée” 2018 or Retouching label “Photographie retouchée” – A tour through France.