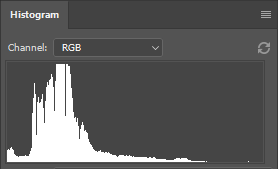

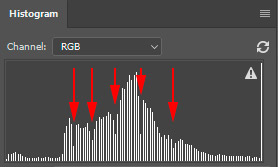

We understand the issue at hand – you want to ensure your edited image is clean and print-ready, and therefore, seek appropriate resharpening techniques. Typically, most people tend to open a sharpen filter and adjust the radius until the image appears acceptably sharp. However, it is important to note that images require more sharpening for printing than for screen playback.

But was everything done correctly? Most likely not.

If you frequently work with images and are skilled in retouching, you can easily identify an image that has been over-sharpened. Often, over-sharpening leads to dry-looking hair and overly sharp skin.

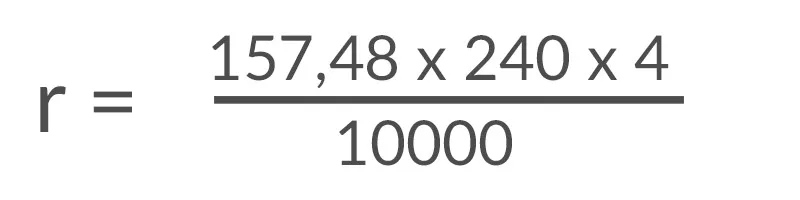

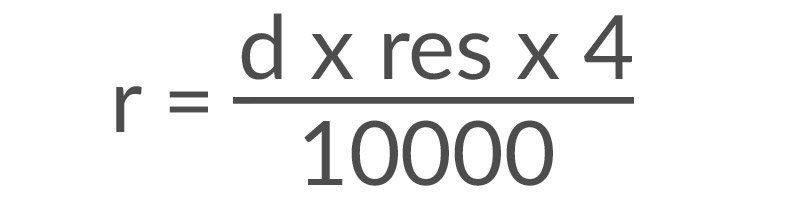

The formula of happiness

Fortunately, there is a formula for printing that provides optimal sharpening!

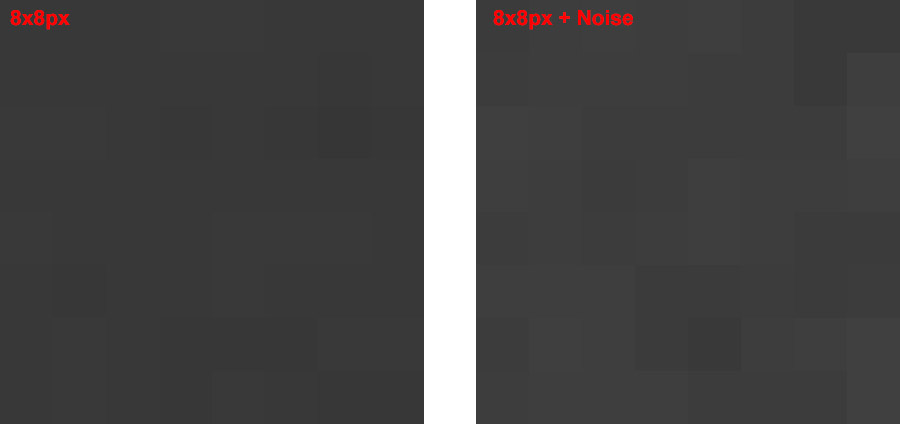

There are several variables to consider when sharpening images:

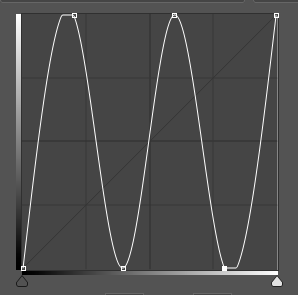

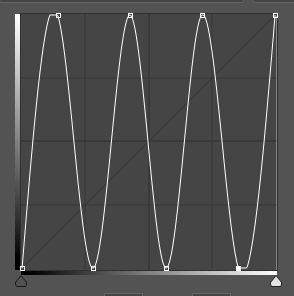

- The first variable is the radius (r). The radius is a value used in Photoshop’s unsharp masking feature, as well as in sharpening methods in Capture One. The goal is to determine the appropriate radius value.

- To do this, we must determine the distance (d) from which the image will typically be viewed. For this formula we use the unit inches for the distance (1 inch is equivalent to 2.54 cm).

- In addition, we measure the image’s resolution (res) – a crucial factor – in dots per inch (dpi).

An Example

Let’s consider an example to see how this works in practice. Suppose I want to display a stunning family picture on my living room wall and aim for maximum sharpness. My couch is located 4 meters away from the picture, and I sit there every day. This viewing distance of 4 meters corresponds to 157.48 inches. Assuming my image has a resolution of 240 dots per inch (dpi), we can perform the following calculation:

The result of the calculation is a sharpening radius of 15.11808, rounded to 15.1 since Photoshop does not allow for precise values.

However, it’s important to use this value with caution because it’s based on the assumption of an optimal print medium, which doesn’t always exist. For instance, if you plan to print on canvas or matte paper, you may need to consult with your print provider. As an alternative use techniques such as smart-objects or sharpening on separate layers for more precise adjustments.

Nonetheless, one important takeaway is that the size of the image doesn’t matter when it comes to sharpness. Only the viewing distance and resolution per inch determine the appropriate level of sharpening.

Background information: Why does viewing distance matter in the sharpening process?

The viewing distance is important because it determines which details our eyes can perceive from a distance, and these details should correspond to the sharpness radius. If you find the idea of manually filling out formulas daunting, you can use a convenient calculator available on the German website www.fineartprint.pro, which is worth bookmarking.

The insights in this article are based on the work of Paul Santek, the operator of the mentioned site. I had the pleasure of attending one of his sessions at the BarCamp event, and I was impressed with his knowledge of printing.

If you missed last week’s blog post, you can find additional information on sharpness here.

If you have any suggestions, additions, or notice any errors in this post, please feel free to leave a comment. We appreciate every recommendation and encourage you to share this post.